Caring for the George P. Hall & Son Collection

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

November 11, 2021

Dozens of photographic techniques have been used over the past 150 years. Before there were digital image files and even before there were film negatives, photographers captured images on glass plate negatives. In the collection of the South Street Seaport Museum there are over 350 of these types of negatives providing detailed depictions of Manhattan and the waterfront edges of the city’s boroughs from ca. 1880s to ca. 1920s. They include views of New York Harbor’s bustling activities, bridges, shipyards, buildings constructions, and street scenes, as well as views of US Navy’s battleships, and land and water celebrations at the turn of the 20th century.

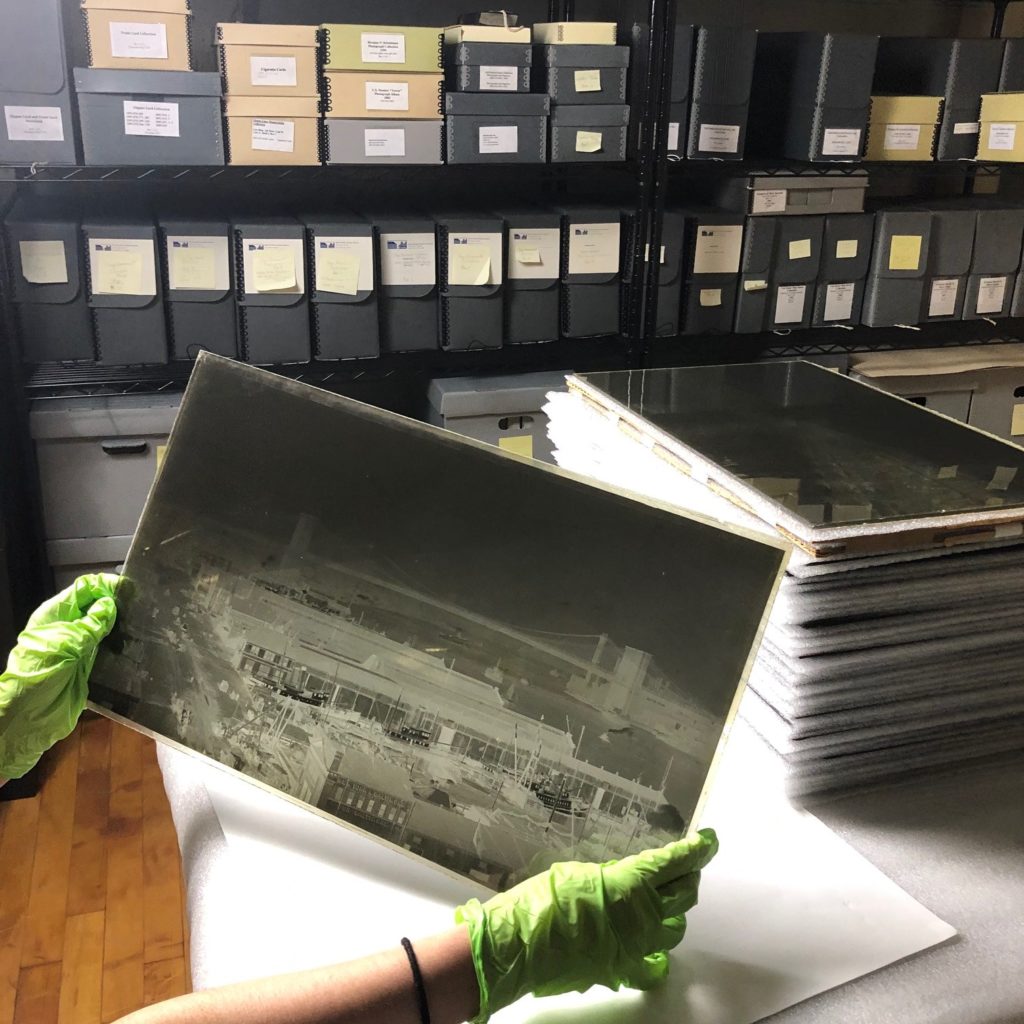

The George P. Hall & Son Collection is just one of many of our negatives collections, and it was recently re-discovered in our archives and storage spaces in Thomson & Co., when objects stored there were relocated prior to the building’s current renovation. These century-old negatives are uniquely large (11 x 19 inches) and were in serious need of cleaning and re-housing. When the negatives went to the conservation lab at Chicago Albumen Works for proper care, the project proved to be a perfect opportunity for their imaging and digitization.

What is a Glass Plate Negative?

As opposed to the type of thin, flexible negatives you may be familiar with, glass plate negatives are exactly what they sound like: a negative printed on a glass plate. There are two different formats for glass plate negatives—the collodion wet plate negative and the gelatin dry plate. Both consist of a glass plate with a light sensitive emulsion fixed to it with a binding agent, which when exposed to light through a camera, creates an image.

Wet plate glass plate negatives were developed in 1851 by the British inventor Frederick Scott Archer (1813-1857) and silver gelatin dry plates were developed in 1871 by English physician Dr. Richard L. Maddox (1816-1902). The terminology “wet” and “dry” literally refers to whether the emulsion on the glass plate was wet when placed in a camera, exposed, and developed, or dry. Photographers had a very short time-frame in which they could use wet plate negatives, approximately 5 minutes. The dry plate method eliminated this time crunch and simplified the photographic process, which led to it very quickly replacing the wet plate method. For an excellent description of the processes of creating and developing these two types of glass plate negatives, I’d recommend you check out this paper available online.

Most of our glass plates, including the ones from George P. Hall & Son firm, are dry gelatine plates. They have crisp black, grey, or clear tones, and they often show a blue metallic sheen, known as “sulphiding out” or “silvering out,” in high-density areas (that is, in the blackest areas of the negative).

Gelatin dry plates were commercially produced and came ready to use. The photographer just had to expose them to light and develop them! The gelatin dry plate negative was widely used from the 1880s until the late 1920s when it was surpassed in both ease and popularity by the gelatin silver negative on celluloid roll film.

Discovery of George P. Hall & Son Plates

In 2019 we moved approximately one third of our holdings from Thomson & Co. to other collections storages on our campus due to a then upcoming, and as of the date of this blog, currently underway restoration of the warehouse building at 213-215 Water Street. 213-215 Water Street was built in 1868 for A.A. Thomson & Co. A transcription error led to the building being referred to as “Thompson Warehouse” in the past. Click here for more details.

This move became the perfect opportunity to revisit every aspect of collections and archives documentation and inventory. Moving a collection is always a very complicated and challenging project, but in many cases it is also an opportunity to improve both the level of care for, and the level of understanding of, a collection.

Throughout the process we in fact discovered and re-discovered artifacts and archival materials that were considered long-lost, and we kind of “stepped back in time” and “into the shoes” former staff members’ curatorial research and fascination for specific aspects of our holdings in the former maritime reference library. One of these passions was clearly negatives.

The amount of film negatives, lantern slides, and glass plates amassed through the last five decades was a captivating and precious discovery; and above all, the negatives from George P. Hall & Son firm were some of the more sensational ones, mostly because of their large size and stunning depictions.

Provenance

Our 44 glass plate negatives from George P. Hall & Son were donated in 1976, together with a life ring from the United Fruit Company, by Mr. Frank J. Sevin, in honor of his good friend, Hudson River enthusiast, and Clearwater supporter, Mr. Otto Verne. At the time of donation, only the life ring was given an accession number and recorded as part of the collection. The glass plate negatives were acknowledged on the Deed of Gift, but were not assigned any inventory number, and were transferred to the Library, without any related documentation.

After we found them, we took some reference images (seeing above) with our cellphones and started to research the negatives. All of our plates match the George P. Hall & Son Photograph Collection at New-York Historical Society, and we are currently working with them in identifying and adding more research in both our institutions’ records. Thanks to the following information at The New-York Historical Society we were able to identify our plates and add more context to this donation and each one of our artifacts.

“The commercial photography firm George P. Hall & Son operated in Manhattan from 1886 through 1914. Working out of several studios, the firm documented the changing face of New York City at the turn of the 20th century. Hall & Son’s photographs were available for general sale, were published in their own calendars and souvenir viewbooks, and appeared as illustrations in publications such as King’s photographic views of New York, Staley’s views of New York, and Harper’s Weekly.

George P. Hall (1832-1900) was born in 1832 in Troy, Ohio, and began his career in 1854 as a daguerreotypist in Dayton, Ohio. A year later he opened his first gallery in Indianapolis and then worked in St. Louis, before finally making his way to New York around 1872. He started his commercial photography business at 78 Fulton Street around 1875, and was officially joined by his son James S. Hall in 1886 when the firm took the name George P. Hall & Son. The father and son operated the company until 1900, when George P. Hall died. James S. Hall continued to run the business until about 1914. It is presumed that the firm closed in the wake of financial difficulties.

The Halls made their residences in Brooklyn, and often turned their cameras toward features of that city as well as Manhattan. They also worked as marine and engineering photographers.”[1] New-York Historical Society, Guide to the George P. Hall & Son Photograph Collection, [1876-1914], PR 24.

Highlights

It is nearly impossible to choose favorites among the 44 glass plates of this collection, but for the purpose of highlighting just a few, I picked negatives covering three major thematic areas of the collection.

South Street and the Brooklyn Bridge

“South Street and Brooklyn Bridge” ca. 1912. Donation in memory of Otto Verne, 1976.004.0003

I would call this a quintessential image representing the Seaport; it embodies the meaning, mission, and vision of our institution. This plate depicts a busy South Street ca. 1912. The piers facing the river are covered, South Street appears busy as does the East River, crossed by tugboats and ferries. The background is characterised by the profiles of the Brooklyn Bridge, Manhattan Bridge, and Williamsburg Bridge, enclosing the scene.

The plate shows the result of the port of New York’s rise to greatness, its many decades as the busiest port in the world, the transformation of the port by technological advances, such as steam and bridges, and the development of the South Street Seaport Historic District in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Bridge Construction

“The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge… is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world.” – Nick Carraway, The Great Gatsby

“Queensboro Bridge under construction, viewed from the south end of Blackwell’s Island” ca. 1909. Donation in memory of Otto Verne, 1976.004.0037

The Queensboro Bridge is one of New York City’s most iconic bridges, and while it may not receive enough attention, it has been a part of America’s popular culture for decades. This glass plate depicts the Queensboro Bridge close to its construction in ca. 1909, from the south end of Blackwell’s Island (today’s Roosevelt Island.) The photograph was taken from the roof of a building on the island, and shows others buildings, including the Smallpox Hospital.

As seen here, somewhat unusually, the bridge actually consists of three separate spans (the space between the support towers on a bridge) —one between Manhattan and Roosevelt Island, one spanning Roosevelt Island, and one connecting Roosevelt Island to Queens. By contrast, the Brooklyn, Manhattan, George Washington, and Verrazano Narrows bridges are all single-span bridges. When built, between 1900 and 1909 it was the longest cantilever span bridge in North America.

Street Scenes

“Wall Street looking west from South Street” ca. 1905. Donation in memory of Otto Verne, 1976.004.0028

While Wall Street was once just a street in lower Manhattan in the 17th century, today the term has come to mean much more. Now it refers to the businesses directly related to stock exchanges and the financial markets, and even more broadly, big business and investing in the United States.

This plate shows Wall Street ca. 1905 when the street was bustling with horse-drawn carts, the elevated train tracks crossed overhead, and Trinity Church still rose above many of the buildings of the Financial District. In the lower right corner you could also see a group of men, in hats and suits, coming off the ferry from Brooklyn, most likely early financial district commuters. This photograph captures a time when Wall Street was still paved with stones and South Street still had tracks for streetcars and it shows the vanishing New York that we all sometime dream to see and experience.

Preservation and Storage of Glass Plate Negatives

The two greatest factors that affect glass plate negatives are relative humidity (RH) and aggressive chemical reactants. Fluctuations in relative humidity and corrosive aggressive chemicals determine the longevity of glass plate negatives.

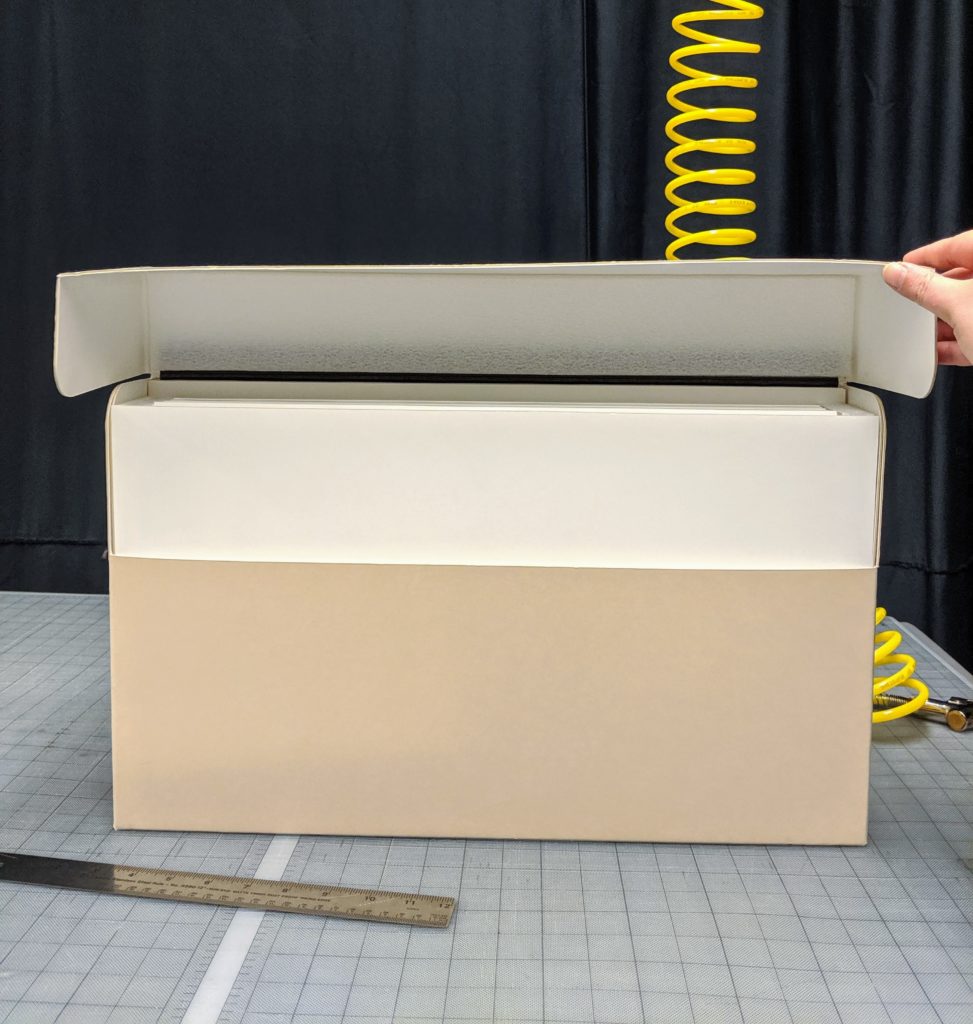

Glass negatives should be kept in an environment with RH levels between 20%- 50%, but preferably below 40%. The recommended temperature is between 59F and 77F, but preferably below 68F. Negatives should be stored in the dark in individual filing enclosures and boxes, to protect them from prolonged exposure to light. They should be stored vertically in tightly packed manuscript boxes or in a box equipped with grooves made from a rigid plastic or metal coated baked enamel.

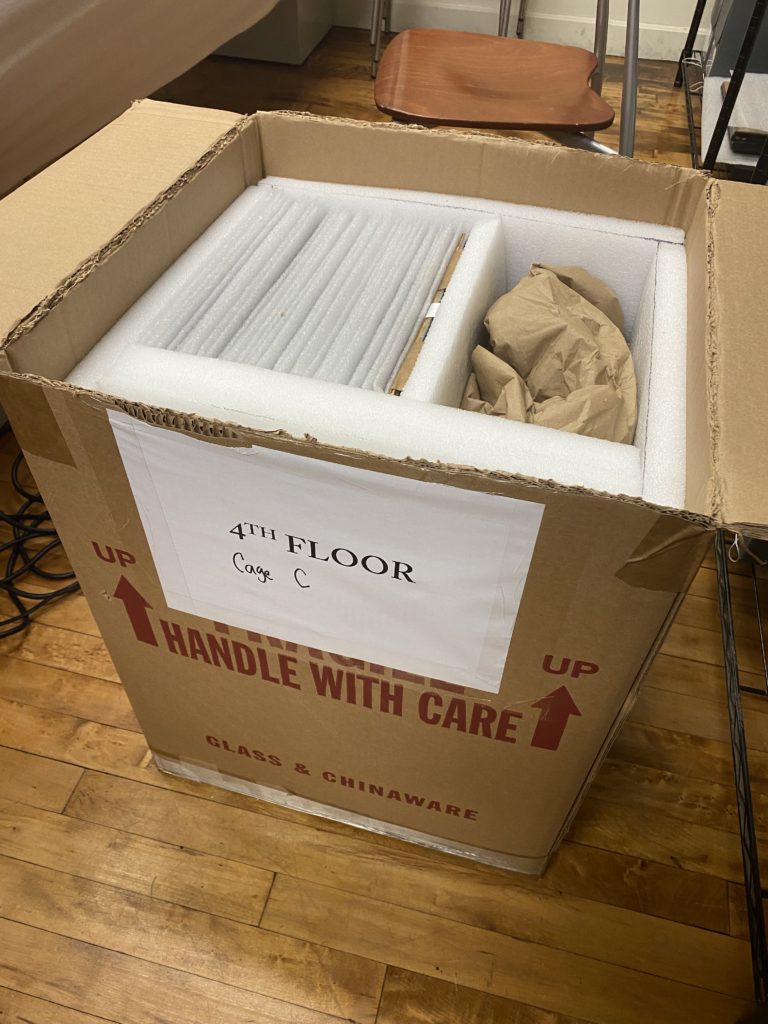

When we found the Hall plates, they were not stored in proper sleeves and boxes, and we quickly, but temporarily re-packed them for the move vertically in a larger box, until funds and time allowed us to properly rehouse and clean them.

At Chicago Albumen Works Inc. the plates have been re-housed, conserved, and digitized, and the digital capture of the negatives provided us with robust image files that would serve almost any practical need from archive, production and exhibitions, to database, and web use.

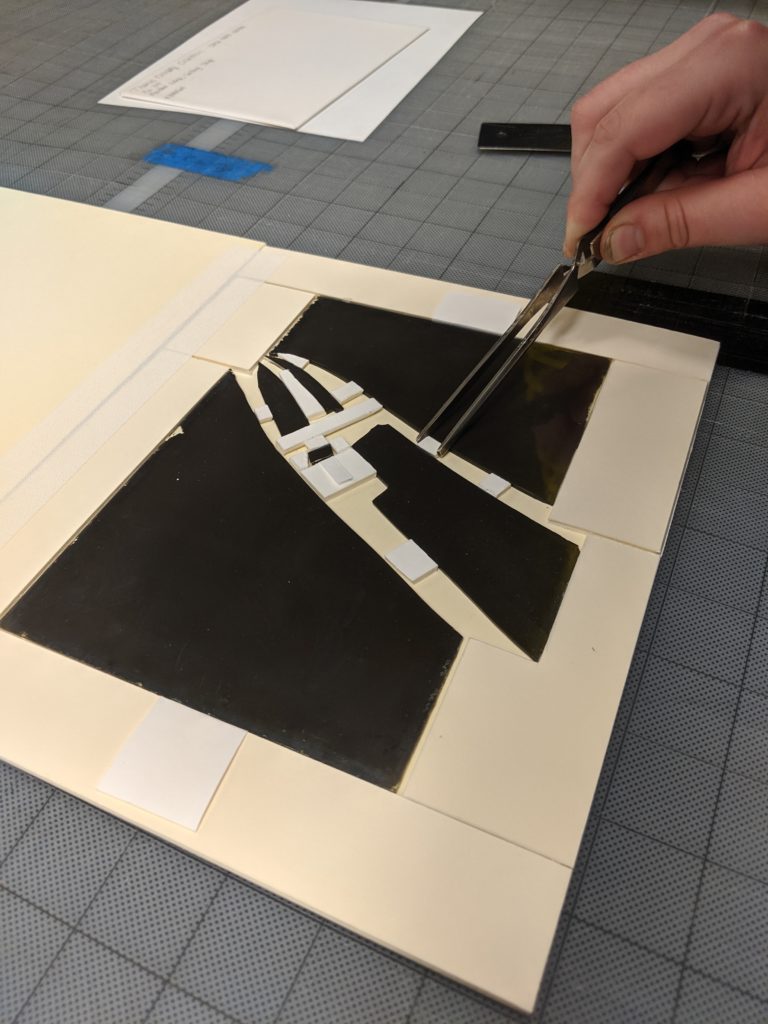

In previous decades, museums and archives would produce physical positive prints from their glass plate negatives. Today, in order to preserve the fragile image layer on irreplaceable glass plate negatives, this process is no longer accepted, but conservators can create high resolution positive digital images with calibrated input devices like scanners and cameras. This also allows images from broken glass plate negatives to be digitally reconstructed without attempting to glue, or otherwise physically repair, shattered glass.

A few of our plates were indeed and unfortunately cracked, and presented some minor losses at corners and edges, but there are no cost effective methods of repairing broken glass plates. Even with the experimental techniques attempted by photograph conservators during training, it is physically implausible to re-assemble more than two or three pieces. So, as a practical matter, since we no longer make traditional photographic prints from negatives, there is no incentive to attempt a physical repair of broken plates. The accepted conservation routine is to digitize broken plates without repair, and preserve the broken pieces in so-called sink mats, as seen below.

Conservation treatments and rehousing, courtesy of Chicago Albumen Works, Inc.

Conclusion

The preservation of glass plate negatives is not without its challenges. As you have read and heard, photographic materials on glass supports are prone to cracking, braking, and flaking of their emulsion, so treatment may not always be an option. For this reason, proper housing and implementation of preservation methods are used to prolong the longevity of the collections. Digitization of materials allows for increased access with minimal need for further handling.

The George P. Hall and Son Collection was an incredible discovery, mostly because such large glass plates survived intact. The preservation and survival of these glass plate negatives seems somewhat remarkable given the fragility of the glass itself and the common 19th century practice of “plate recycling.” Throughout the 19th century, local junk men would purchase old, unwanted glass plates, scrape off the photographic emulsion and resell the glass to greenhouses and dry-plate manufacturers. The dry plate manufacturers readily purchased this glass, as it could be easily reused and was already cut to standard photographic sizes.

As we continue to inventory the materials we packed and transferred to our main building two years ago, including this collection of glass plate negatives, we find ourselves in the midst of solving mysteries brought up by the move. We are definitely in a better place than where we started, and we are constantly delighted by the materials we catalog, digitize, and make available to the public via a variety of digital platforms including this blog, our Collections Online Portal, and our social media channels.

Additional readings and resources

“The life of a photograph: archival processing, matting, framing and storage.” L.E. Keefe, and D. Inch, published in Focal Press, Boston, 1984.

“Preservation of 19th-Century Negatives in the National Archives” by Constance McCabe, published in Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 30, 1991, pp. 41–73.

“A Guide to the Preventive Conservation of Photograph Collections” by B. Lavédrine, J.-P. Gandolfo, and S. Monod. Getty Conservation Institute, 2003.

“Glass slide negatives.” by S. Vail, published in The Scream Online: A Magazine for Art, Photography, Literature” Fall/October 2002.

“How Do I House Glass Plate Negatives?” published in the U.S. National Archives website.

“Trip the Light Fantastic: A Conscientious and Compelling Display of a Glass-Plate Negative” by Christina Finlayson, published on the National Portrait Gallery website.

“Saved from a dumpster, glass negatives reveal life in Mass. more than 100 years ago” by C. Muther, published in the Boston Globe, July 15, 2021.

References

| ↑1 | New-York Historical Society, Guide to the George P. Hall & Son Photograph Collection, [1876-1914], PR 24. |

|---|